The evening of March 29th, 1943. A young crew of 7 board their Short Stirling bomber with serial BK716 for their third mission. Target is Berlin. A feared destination, because of the heavy defence. And indeed BK716 disappears. For decades nobody knows what happened to them, until last year.

Only three months before, in February 1943, Flying Officer Harris and his crew graduated from the 1657 Heavy Conversion Unit (HCU) at RAF Stradishall in Suffolk. They were assigned to 218 ‘Gold Coast’ squadron, based at Downham Market in Norfolk. Like all men flying for Bomber Command, they were volunteers. And they must have been brave man, as they knew the risks they faced when they stepped into a plane. During World War II, no less than 44% of Bomber Command air crew (totalling 55,573 men) were killed in action over the skies of Europe, the highest rate of attrition for any allied unit.

Harris’ crew consisted of:

- Flying Officer John Frederick Harris (GB, pilot, 29)

- Sergeant Ronald Kennedy (GB, flight engineer, 22)

- Flying Officer Harry Gregory Farrington (Canada, observer, 24)

- Sergeant Charles Armstrong Bell (GB, wireless operator/air gunner, 29)

- Flying Officer John Michael Campbell (GB, air bomber, 30)

- Sergeant Leonard Richard James Shrubsall (GB, air gunner, 30)

- Flying Sergeant John Francis James McCaw (Canada, air gunner, 20)

On March 29th around 21:30 h in total 329 aircraft, including Stirling BK716 flown by Harris, take off from their respective bases for a night raid against Berlin. However no less than 120 of them are forced to return early, because of bad weather over the North Sea. The others meet fierce resistance from German night fighters over The Netherlands, and 9 aircraft are shot down. The rest make it to Berlin and manage to drop their bombs, making the mission a tactical success. However, the FLAK and again German fighters on the way back cause the loss of another 12 aircraft.

Luftwaffe Leutnant Werner Rapp of the 7th Gruppe of Nachtjagergeschwader 1 (7./NJG 1) flies his Messerschmitt Bf-110G-4 with squadron code G9+CR from Twenthe airbase in The Netherlands. When the bombers return from Berlin, he is waiting for them. First he manages to shoot down Lancaster ED761, after which German radar station ‘Hase’ near Harderwijk directs him to a lower flying bomber at 4,300 meter. This is Stirling BK716, that is unable to escape. When back at his base, Lt. Rapp reports shooting down ‘unknown Stirling, 2-4 km East-Southeast of Marken Island’. BK716 is the last of the raid to be shot down, although at the time nobody knows what happened to them.

In 2008 a private yacht gets into trouble while sailing on the Markermeer. When they get rescued by the Royal Netherlands Sea Rescue Organisation, part of the landing gear of an aircraft gets stuck on their anchor. This is identified as a piece of a Short Stirling bomber. Divers find another piece and a wooden mascot, both of which seem to indicate the aircraft in question is Sterling BK710. No attempt to lift the wreckage is made yet. Years later further research and the recovery of some small artefacts point in the direction of BK716. Amongst others a cigarette case is found with initials JMC. BK710 had no crew member with those initials, but on board of BK716 was John Michael Campbell. No definitive proof is found though.

In 2018 the Dutch government decides to fund a ‘National Program Salvage Aircraft Wrecks’. The intention is to salvage some 30-50 wrecks all over the country that possibly still have human remains inside and are classified as a potentially successful salvage. Major Bart Aalberts of the Royal Dutch Air Force is in charge of the program: “We hope to find the remains of the missing crew members. That way, after all these years, their relatives get final certainty and can say goodbye. And justice is done to the ultimate sacrifice that these crews made for our freedom.”

During the salvage, Major Bart Aalberts is assisted by his, now civilian, predecessor major (retd.) Arie Kappert. Kappert explains: “Before the actual salvage started, the whole area has been searched using radar, sonar and iron detection. That way an area of 75 by 75 meters is designated the main search area with another smaller area of some 10×10 meters nearby. All interesting bits are mapped using GPS, ready for salvage.” After a delay of a few months because of safety issues, at the end of August 2020 the actual digging started. For this a digger is placed on a pontoon. The digger is equipped with GPS, so exact position and depth can be determined with an accuracy of 5 cm. All the material that comes to the surface is first sifted over a sieve of 30 cm. This is because of safety, as it is not known whether the aircraft was able to drop its bomb load before the crash. Luckily no bombs are found, making it clear flying officer Harris and his crew at least were able to fulfil their mission before being shot down.

All the material then goes to another nearby pontoon where it is sifted over a sieve of only 8 mm. Everything is meticulously scanned by a team of four people, consisting of a radiation expert (aircraft instruments were painted with radioactive paint), an ammunition specialist (lots and lots of ammo for the board guns was found), an archaeologist and last but not least an expert on human remains.

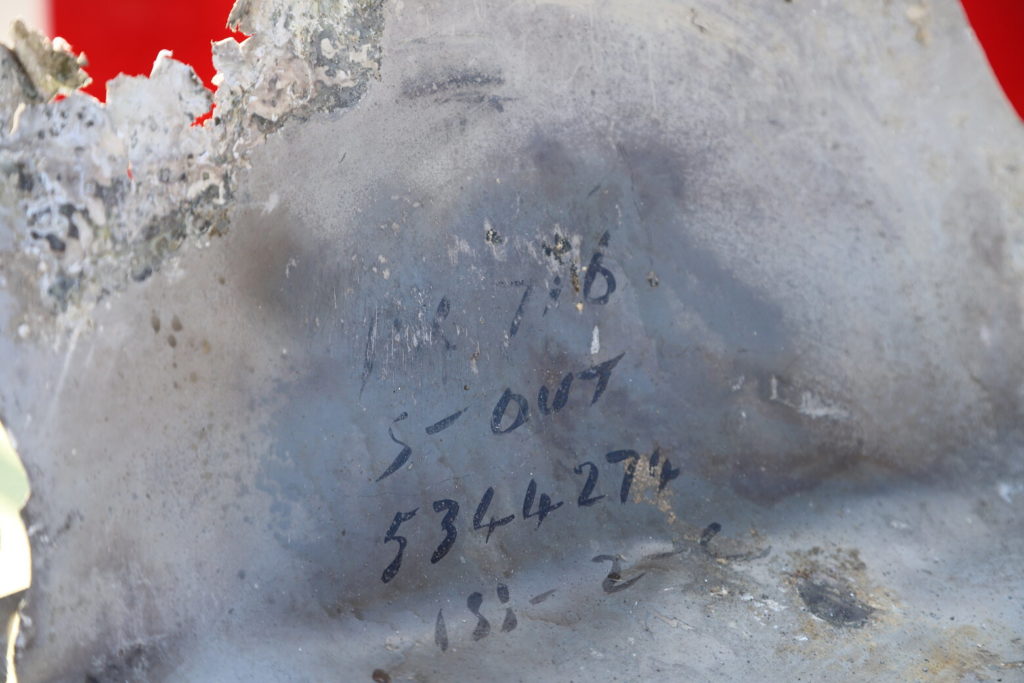

Already in the first week an engine is found and its serial number finally confirms the identity of the Stirling as BK716 without a doubt. In the end all four engines are dug up, both main landing gears, cockpit instruments, fire extinguishers, oxygen bottles, a very rare complete fuel tank and large parts of wings and fuselage. One panel still shows hand written serial BK716 on the inside. But more important, also lots of human remains have been found. Because of the impact of the crash on the water surface, these are very small. And because of the number and their age, DNA research is no option anymore. Identification will therefore be done by examining the so-called MNI or Minimum Number of Individuals. If the experts are able to tell the remains of seven different people have been found, all crew members are accounted for. In that case all will probably get their own grave stone. If not, most probably all remains will be buried together and there will be a single stone for the complete crew. This herculean task of identifying all found remains is performed in Soesterberg by specialists from the Dutch army, led by Captain Geert Jonker, and will take several months at least.

The team closely cooperate with the British Joint Casualty and Compassionate Centre, who in turn are in close contact with their Canadian counterparts because two of the missing crew members were Canadian. Harry Farrington is one of them, and his 93 years old sister Edith McLeod is very happy she will finally get some answers on the fate of her brother. “I think it is marvellous. (…) We basically knew he was shot down. And that was all we knew.” The family had assumed he was shot down over Germany, but now they have learned he actually completed his mission and was on his way back.

It is to be hoped the experts will indeed be able to determine an MNI of 7, so all families can lay there beloved ones to rest after all this time. They and all other dedicated people involved deserve it, that’s for sure.

This article has also been published in Aviation News Journal magazine.

We would like to thank the Royal Dutch Air Force, the Gemeente Almere, 218 Squadron Association and Aircrew Remembered for their assistance.